December 22 sees the commemoration of an Irish saint with an interesting Lenten discipline – Ultan Tua ‘the Silent’ of Clane, County Kildare. The Martyrology of Oengus records:

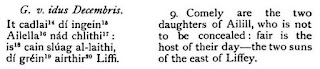

22. May Tua’s prayer which is not speech, protect us (and) Itharnaisc, with bright Emene from the brink of silent Berbae.

to which entry the scholiast has noted:

22. May Tua’s prayer protect me, i.e. Tuae from Tech Tuae in Hui Faelain, the same as Ultan of Tech Tuae. Idea Tua ‘silent’ dicitur etc.

The later Martyrology of Donegal records the ascetical practice Saint Ultan pursued during Lent which gave rise to his reputation as the quiet man:

22. F. UNDECIMO KAL. JANUARII. 22.

ULTAN TUA, and IOTHARNAISC, two saints who are at Claonadh, i.e., a church which is in Ui Faelain, in Leinster. This is the Ultan Tua who used to put a stone in his mouth in the time of Lent, so that he might not speak at all.

Father Michael Comerford, in his diocesan history of Kildare and Leighlin, records something of the locality in which these saints flourished, and notes a tradition that they were brothers to another monastic, Maighend, abbot of Kilmainham. He claims though that the Martyrology of Donegal gives their feast at December 23, but as we have seen above, they are listed at December 22:

PARISH OF CLANE.

THE Parish now so called comprises the ancient parochial districts of Clane, Mainham, Dunadea, Timahoe, Dunmurghill, Ballynefah, and Balrahen.

CLANE.

In ancient records the name of this place is given in two forms; Claen-Damh, i.e., “the field of oxen;” and Claen-Ath, i.e., “the field of the Ford.” It is referred to in the Forbais Edair, “The Siege of Howth,” an ancient historic tale, which Professor O’ Curry treats of in his 12th Lecture (MS. Materials of Irish History). This passage is summarized in the Loca Patriciana, (note p.113). The Ford of Clane was in the first century the scene of the tragical death of Mesgegra, King of Leinster, who fell here in single combat with Conall Cernach, the champion of Ulster, who had pursued him hither whilst flying from the siege of Howth. Aithirne, the Ultonian poet, surnamed Ailghesach, or the Importunate,-so called from the fact that he never asked for a gift or preferred a request but such as it was especially difficult to give or dishonourable to grant,-had been sent to the court of the King of Leinster at Naas, for the purpose of picking a quarrel with the people of that Province. He had been hospitably received by King Mesgegra, and had many gifts bestowed on him; but this only made him the more importunate, and at last he insisted on getting 700 white cows with red ears, a countless number of sheep, and 150 of the wives and daughters of the Leinster nobles to be carried in bondage into Ulster. To these tyrannical demands the Leinster men apparently submitted; but having pursued Aithirne to Howth, they rescued their women. The Ulster men, however, having been reinforced, the Leinster forces were routed. Conall Cearnach, the most distinguished of the heroes of the North, pursued Mesgegra to take vengeance for the death of his two brothers who had been slain at Howth. He overtook him at the Ford of Clane, where a combat ensued between them in which Mesgegra was slain and beheaded. Conal placed the king’s head in his own chariot, and, ordering the charioteers to mount the royal chariot, they set out northwards. They had not, however, gone far, when they met the queen of Leinster, attended by 50 ladies of honour, returning from a visit to Meath. “Who art thou, O woman?” said Conall. “I am Mesgegra’s wife,” said she. “Thou art commanded to come with me,” said Conall. “Who has commanded me?” said the queen. “Mesgegra has,” said Conall. “Hast thou brought me my token?” said the queen. “I have brought his chariot and horses,” said Conall. “He makes many presents,” said the queen. “His head is here, too,” said Conall. “Then I am disengaged,” said she. “Come into my chariot,” said Conall. “Grant me liberty to lament for my husband,” said the queen. And then she shrieked aloud her grief and sorrow with such intensity that her heart burst, and she fell dead from her chariot. The fierce Conall and his servant made there a grave and mound on the spot, in which they buried her, together with her husband’s head, from which, however, he extracted the brain. This queen’s name was Buan, or the Good (woman); after some time, according to a very poetical tradition, a beautiful hazel tree sprung up from her grave, which was for ages called Coll Buana, or Buan’s hazel. The Tumulus beside the river at Clane is supposed to mark the grave of King Mesgegra and his queen. (O’ Curry, p. 170, & seq.)

A Monastery was founded at Clane at a very early period. Colgan refers to a Church having been here before the middle of the sixth century. It is recorded that St. Ailbe of Emly, whose death is assigned in our Annals to have taken place in the year 527, resided here for some time, and, on leaving, presented his cell to St. Senchell, who afterwards founded a monastery at Killeigh, and died there on the 26th of March, 549.

The Martyrology of Donegal, at May 18th, records “Bran Beg of Claenadh, in Ui-Faelan, in Magh-Laighen,” and at Decr. 23rd, “Ultan-Tua and Jotharnaise, two Saints who are at Claonadh, i.e. the Church which is in Ui-Faelain, in Leinster. This is the Ultan-Tua who used to put a stone in his mouth at the time of Lent, so that he might not speak at all.” Fr. Shearman, Loca Pat., remarks that Taghadoe, i.e. Teach Tua, or “Tua’s house,” near Maynooth, would mark his connexion with that locality rather than with Clane; but he might have been, as then was usual, abbot of both communities. These two Saints were brothers of Maighend, Abbot of Kilmainham, and were sons of Aed, son of Colcan, King of Oirgallia, vivens A.D. 518. Aed became a monk at Llan Ronan Find, where he died, May 23rd, 606. These dates throw some light on the Monastery of Clane. (Note, p.114.)

A.D. 702. A battle (was fought) at Claen-ath, by Ceallach Cuallann, against Fogartach Ua Cearnaigh who was afterwards King of Ireland, wherein Bodhbhehadh of Meath, son of Diarmid, was slain, and Fogartach was defeated. (Four Masters.) In the Annals of Ulster this event is thus recorded:-“A.D. 703. Bellum Cloenath, ubi victor fuit Ceallach Cualann, in quo cecidit Bobhcath Mide mac Diarmato. Fogartach nepos Cernaig fugit.”

A.D. 777, (recte 782) Banbhan, Abbot of Claenadh, died. (Four Masters.)

A.D. 1035. Clane was plundered by the foreigners; but the son of Donnchadh, son of Domhnall, overtook them, and made a bloody slaughter of them. (Id.)

A.D. 1162. A Synod of the clergy of Ireland, with the successor of Patrick, Gillamaclaig, son of Ruaidhri, was convened at Claenadh, where there were present twenty-six Bishops, and many Abbots, to establish rules and morality amongst the men of Ireland, both laity and clergy. On this occasion the clergy of Ireland determined that no one should be a lector in any Church in Ireland who was not an alumnus of Ard-macha (Armagh) before. (Id.) The following is a passage from Colgan on this subject:- “Concilium Cleri Hiberniae, praesidente Comorbano Patricii, Gelasio Roderici filio, servatur in loco Claonadh dicto; in quo comparuerunt viginti-sex Episcopi, et plurimi abbates; et praescriptae sunt tam clero quam populo Hiberniae constitutiones, bonos mores, et disciplinam concernentes. Illa etiam vice clerus Hiberniae sancivit ut nullus in posterum in ulla Hiberniae Ecclesia admittatur Faerleginn (id est, Sacrae Paginae seu Theologiae Professor) qui non prius fuerit alumnus, hoc est, Admachanam frequentaverit Academiam.” (Trias Th., p. 309.)

A more recent writer has commented on the locality Tech Tua:

Taghadoe (Tech Tua), however, is named for another saint, Ultan Tua (the Taciturn Ulsterman). The Taghadoe settlement had strong links with Clane and at one time shared its abbot with the Clane monastery.

Hermann Geissel, A Road on the Long Ridge-In Search of the Ancient Highway on the Esker Riada (Newbridge, 2006), 12.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.