A County Down monastic saint, Bití (Bitus, Bite) of Inis Cumscraigh, is commemorated on the Irish calendars on July 29. Inis Cumscraigh is today known as Inch, which as the name suggests was once an island on the River Quoile but is now on land close to the town of Downpatrick. It boasts some very impressive and extensive Cistercian monastic ruins. Inch Abbey was founded in the 1180s by the self-styled ‘Prince of Ulster’, John de Courcy, following his conquest of the area. It was a daughter-house of the Cistercian foundation at Furness in Lancashire, from whom de Courcy commissioned the hagiographer Jocelyn to write a Life of Saint Patrick. I have written about de Courcy, Jocelyn and Saint Patrick in a post at my blog dedicated to the Irish patrons here. But today’s native Irish saint pre-dates both the Normans and the Cistercians. In a 1977 paper archaeologist Dr Ann Hamlin, drawing on the evidence from the Irish calendars and Annals, provided a useful sketch of the history of the pre-Norman monastery at Inch:

An earlier name for the island was Inis Cumhscraigh, and it was the site of a pre-Norman monastery. ‘MoBíu of Inis Cúscraid’ is listed at 22 July in the main text of the Martyrology of Oengus, and the entry is glossed ‘i.e. beside Dún dá lethglas’, whilst in the Martyrology of Tallaght ‘Dobí of Inis Causcraid’ appears at 29 July. The Martyrology of Oengus was written between 797 and 805 and the Martyrology of Tallaght a little earlier, so these references provide firm evidence for a pre-Viking church on the island. Several annal entries refer to the site in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. In 1001 ‘Sitric, son of Amhlaeibh, set out on a predatory excursion into Ulidia, in his ships, and he plundered Cill-Cleithe [Kilclief] and Inis-Cumhscraigh, and carried off many prisoners from both (Annals of the Four Masters, also Annals of Tigernach). The Annals of Ulster record the death of ‘Ocan Ua Cormacain, herenagh of Inis Cumscraigh’ in 1061, and in 1149 Inis-Cumscraidh was plundered together with other churches in the area (AFM). The erenagh of Insecumscray was among the witnesses to the foundation charter of Newry abbey in about 1153. These references collectively suggest that a church and perhaps some form of monastic life did continue on the island into the twelfth century.

Ann Hamlin, A Recently Discovered Enclosure at Inch Abbey, County Down, Ulster Journal of Archaeology Third Series, Vol. 40 (1977), 85-86.

Saint Bití is the second saint named in connection with this monastery with a feast falling just seven days (and thus within the octave) of that of Saint MoBíu commemorated on July 22. Canon O’Hanlon, in his entry for July 29 in Volume VII of his Lives of the Irish Saints feels that they are probably the same person:

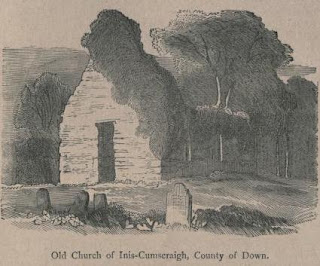

Festival of St. Bitus or Bite, of Inis Cumscraigh, now Inch, or Inniscumhscray, Strangford Lough, County of Down.

According to the Martyrology of Tallagh, veneration was given, at the 29th of July, to Bitus or Bite, of Innsi Caumscridh. This holy man is called Bute, or perhaps Byte, by Marianus O’Gorman. That island or rather peninsula is beautifully situated in Strangford Lough, and nearly opposite to Downpatrick, county of Down. Some interesting ruins are yet seen in this place. An abbey or a monastery stood here – as has been already observed – before the erection of one, which has been founded by the Anglo-Norman warrior, John de Courcey. When the present saint flourished has not been ascertained. In the Martyrology of Donegal, we find an entry of Bite of Inis Cumhscraigh, at the 29th of July. We are inclined to think, that the present holy man is not distinct from the Abbot so called, and who is celebrated on the 22nd day of this month, where an account of him has been already given.

Canon O’Hanlon’s account of Saint MoBíu can be read at the blog here.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2022. All rights reserved.