On May 8 we commemorate an Irish missionary saint, Gibrian, whom tradition records as a member of a large family of missionary saints who laboured in France. Canon O’Hanlon brings us details not only of the saint’s life, but also of the history of his relics, sadly lost as a result of the impiety of the French Revolution:

St. Gibrian, or Gibrianus, Priest in Champagne, France. [Fifth and Sixth Centuries.]

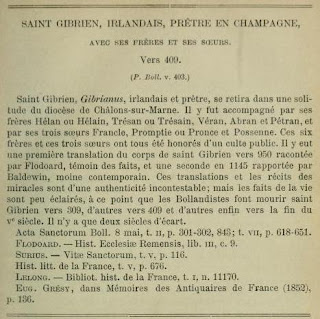

It will be seen, from the following account, that Ireland furnished France with the hallowed influences, brought not alone by the present holy priest, but also by his many brothers and sisters, who were equally desirous of seeking a retreat, in one of her most agreeable districts, there to edify all, by their holy conversation and example, during life; while, after death, the Christian Celts of Gaul venerated their relics, obtaining choice graces and benefits from their intercession. Among the earlier Acts of St. Gibrian is an account, furnished from the special Breviary, belonging to the Head Monastery of St. Remigius; while another eulogium of the saint is to be found, in the Rheims Breviary, printed A.D. 1630. Besides, he is commemorated, in various ancient Martyrologies, and by Flodouard. The Acts of this saint have been published, in five paragraphs, by Surius at the 8th of May. A Life of this holy man was in preparation, but, it was left, unpublished by Colgan, at this date. The Bollandists have the Acts of St. Gibrian, at the 8th of May, and they allude to the Translation of his Relics, in an Appendix. The Rev. Alban Butler, the Circle of the Seasons, the Petits Bollandists, and Rev. S. Baring-Gould mention Gibrian, or Gobrian, a priest, at the 8th of May.

This holy man was born in Hibernia, some time in the fifth century and, as he seems to have lived contemporaneously with St. Patrick, it is not improbable, that himself and the other members of his numerous family received baptism, at the hands of the Irish Apostle, or, at least, from the ministration of someone, among his disciples. It would appear, that in Ireland, St. Gibrian had been elevated to the priesthood. He chose, however, to serve God, in a more distant country; and, it is related, that about the close of the fifth century, he left home for the Continent. Six holy brothers and three sisters accompanied him to France. Their names are given, as Tressan, Helanus or Helain, Germanus, Veran, Abranus and Petranus, his brothers; as also, Franchia, Promptia and Possenna, his sisters. St. Gibrian, with his brothers and sisters, is said to have arrived in France, according to a Breviary of Rheims, in the time of Clovis I., and of St. Remigius. His arrival is placed, at A.D. 509, by Sigebertus Gemblacensis. It is thought to be probable, that those holy pilgrims sojourned, at first, in Bretagne; for, in this French province, many localities are called after them. There is a parish, known as St. Helen; a parish is named St. Vran; a parish and various other places are dedicated to St. Abraham—probably the same as Abram—the strand of St. Petran, and the grotto of the same saint, in Trezilide, have supposed relations with these Irish visitors to France. However, the pious brothers and sisters regarded St. Gibrian, as their leader; because he had received Holy Orders, and because he was the oldest among them. He sought for settlement theterritoryabout Chalons-sur-Marne, and fixed his dwelling near a rivulet, called Cole, which flows into the River Marne. On account of St. Gibrian’s great sanctity, his habitation was the chief rendezvous for his brothers and sisters. He was especially the companion of the brother, named Tressan, who lived in a retired village, supposed to be Murigny, in the former Duchy of Rheims, and on the River Marne. A strong family attachment bound the saintly brothers and sisters to each other; so that, mutually desirous of visiting frequently their solitary places of retreat, these were selected within measurable distances, in this part of the country. Gibrian’s love for prayer and for labour was most remarkable. He was indefatigable in the exercise of all virtues; while his abstinence from food was a means he adopted, to render his life still more spiritual. Having led a very holy state, in the district of Chalons-sur-Marne, in Champagne, Gibrian died there, and he was buried in the place of solitude he had selected for his home while upon earth. That spot was indicated, by a sort of tumulus, or mound, near the public road. A stone sarcophagus had been prepared, to enclose his body, which was then deposited in the earth. There, his memory is revered, on the 8th day of May, which was probably that of his death, or as it is said of his deposition. A small oratory was built over his tomb, in course of time.

On the anniversary of his happy departure, a great concourse of persons usually came to celebrate the occurrence, and it was converted into a religious festival. Soon after his departure, the Almighty was pleased to work great miracles, when the name and intercession of his holy servant had been invoked, by the faithful pilgrims. These kept vigil, with prayers or hymns, the night before his anniversary feast; they also brought votive offerings; and when the sacred offices of Mass were over, on the day itself, all the people returned with rejoicing to their several homes. However, this saint is said by some to have died at Rheims, A.D. 509 ; but, this appears to have been supposed, because his remains were subsequently removed to that city. In the time of Otho, King of France, the Danes and Normans brought terror and destruction among those Christians, living in the district about Chalons; while they burned churches and villages, and also put many to the sword. They set fire to the beautiful cathedral church of St. Stephen, in the city of Chalons, and also to the little oratory of St. Gibrian; but, as his relics were sepulchred in the earth below it, these fortunately escaped their ravages. Afterwards, while travellers journeyed by that spot, the sweetest sounds of music were heard by them, and as if these were issuing from St. Gibrian’s grave; while, the sentinels on guard within the fortifications of Chalons reported, that they had frequently observed bright lights streaming over Cole. Such portents caused a general popular veneration for the holy exile, whose body still lay there. Afterwards, the religious Count Haderic obtained permission, from Ródoard, bishop of Chalons, that he might remove the body of St. Gibrian to a place, where suitable honour might be rendered. His remains, in the latter end of the ninth century, were accordingly removed to Rheims. From Chalons, they were brought first to the village of Balbiac, where for three years, they were honourably preserved, and, afterwards, they were removed to that city, selected for their final deposition.

In those days, the removal of a saint’s remains from one place to another was reluctantly submitted to by the people, among whom they had been preserved; and, this will probably account for the secrecy observed, on that occasion, when it was resolved, to take St. Gibrian’s body away by night. A boatman had been ordered to have his skiff in readiness, before the dawn of day, and near the holy man’s place of sepulture on the river’s side. A priest and three men, sent by the Count, were waiting the boatman’s arrival; but, notwithstanding frequent shouts to guide him near their station, the skiff appears to have got aground, on the opposite bank, nor could it be moved. The priest and his companions then devoutly prayed, that means should be furnished them, to remove the body. As if by miracle, the skiff was detached from its fastenings, and it was driven over where they waited. Next, approaching the tomb, the sacred relics were reverently raised from the sarcophagus, placed in a new shrine, and removed to the boat. When the bones of St. Gibrian had been kept for two years, at Balbiac, Count Haderic and his pious wife Heresinde went on a visit, to the city of Rheims. That removal of St. Gibrian’s remains took place, when Fulco, or Foulques, was Archbishop over the See, and, therefore, some time between 882 and 900, or 901. His noble visitors preferred a request, that the shrine of the saint might be placed, on the right side of his church, near the opening to the crypt. Their petition was granted. The relics were reverently placed, within the basilica of St. Remigius; while, an altar was built, in honour of the holy man, and most beautifully ornamented, even with the precious metals. Here was the noble monastery church, more ancient than the magnificent cathedral, and dedicated to that holy bishop, who was patron of Rheims; and, over the high altar—called the Golden Altar—of this church, the body of St. Gibrian was preserved within a shrine.

When the body had been brought away from Cole, a blind woman, named Erentrude, came to that place, with a candle to present, as her humble offering. Finding that Gibrian’s remains had been removed from his sarcophagus, she asked why the saint had permitted it, or why he should desert the people, who had obtained such great benefits from his patronage. With earnest prayers for her recovery, she then went to the village of Matusgum, where his brother Veran was buried and greatly venerated. There, she deposited her candle on his tomb, and prostrated in tears before it, she prayed to both holy brothers for restoration of her sight. Her petition was granted, and the afflicted woman left the spot, filled with a holy joy, when she again saw the light of day. The body of St. Gibrian was transferred to a new shrine, in the year 1114, and then, too, various miracles took place, while a large congregation was present. The shrine of St. Gibrian was preserved, until the period of the French Revolution; but, at present, both the shrine and its sacred deposit have completely disappeared. At this time, a general system of robbery and plunder was organized in France: in various places, the churches were despoiled of their plate and valuables. Not far from his ancient tomb, in the diocese of Chalons, there is a village, known as St. Gibrien.

On the Continent, the feast of St. Gibrian is commemorated, at the 8th of May, by Usuard, as also in a Manuscript Martyrology of Rheims, and in another Florarius Sanctorum. Besides Greven, Canisius, Saussay, Ferrarius, and Molanus, have his festival entered, for this same date. The Irish and Scotch also celebrate his memory. Thus, Thomas Dempster places him, in his “Menologium Scoticum,” as also, Adam King, in his Kalendar, at this day. In the anonymous list, published by O’Sullevan Beare, at the 8th of May, Gibrianus is entered. He is also noticed, by Father Stephen White. The Irish people cannot learn too much about their European missionaries —those grand pillars of Faith and of truth—whose names stud the pages of Church history, like so many fixed landmarks of a past civilization, in which those servants of Christ have had a glorious share.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.