September 9 is the feast of Saint Ciarán, founder of Cluain Mhic Nóis, Clonmacnoise, County Offaly. Below is an essay by English Catholic writer, Marian Nesbitt, in which she sketches the history of this famous foundation. The later status and importance of Clonmacnoise owed much to its strategic location on the River Shannon, but here we can read the hagiographical account from the Life of Saint Ciarán, with the trope of the saint rejecting other promising locations until he found the site from where ‘many souls would ascend to heaven.’ Clonmacnoise also developed a particular reputation as a centre for learning and Miss Nesbitt describes some of its famous teachers and alumni. She also pays a generous tribute to the debt owed by her own countrymen in the Middle ages to Clonmacnoise, something all the more striking when we consider that this essay collection was published in 1913, when the Home Rule Crisis had strained the relationship between Ireland and Britain to breaking point:

XXII.

A HAUNT OF ANCIENT PEACE.

ON a bare slope in one of the most desolate spots to be found in Ireland stand the grey ruins of what was once an ancient national institution, a great school of learning; and, more than this, “a true and living centre of European culture, to which men’s thoughts turned from far-off events and cities of illustrious kings”. Here, from different countries, came numbers who desired to apply themselves to study; and here scholarship increased side by side with sanctity. We know that St. Columba’s monastery at Iona, whence the light of Christian truth was brought to many parts of Britain, was the most important of all the foundations made outside of Ireland after the time of St. Patrick; and it is almost equally certain that no religious community established in Ireland after that date was so influential as the one which was inaugurated at Clonmacnoise by one of Columba’s younger contemporaries — “the gentle, loving, tender-hearted” Ciaran, who became his intimate friend at Clonard, where they had both been educated.

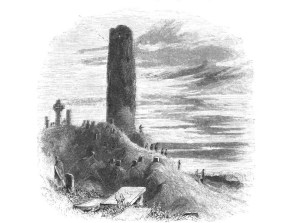

The massed group of buildings and low stone walls, with towers springing out of their midst, sloping up from the lonely stretch of river are, as we have said, all that now remain of once famous Clonmacnoise. There are two round towers there; and it has been suggested by those who, having made a careful study of the subject, can speak with authority, that the presence of these distinctive monuments of time may be explained by the fact that “in a community so exposed, so numerous, and probably so prosperous, more lives and valuables had to be secured than could be huddled in haste into one of the bell-tower fortresses”.

How often, for instance, at Kells, must the alarm have been given from the high tower, one of the finest examples of “those astounding belfries,” as the round towers have been truly called, which were erected all over Ireland in the days when the unarmed inmates of monastic houses needed a place of sudden and safe retreat for themselves and their treasures! We can picture the custodian of the famous Book hurrying in breathless haste up the wooden ladder to the narrow doorway, ten feet above the ground, carrying with him the Book and its cumhdach, or casket; and drawing up the ladder as soon as he and his companions were inside. Then the barbarous hordes of Danes were free to assault at will, with axe or crowbar, the huge round pillar of solid masonry: the Book, that gem of Irish art, which has been described as “incomparably the first among all the illuminated manuscripts of the world,” was safe with the monk who had charge of it, — safe in a building so impregnable that whole armies might have stormed it in vain.

Old documents tell us that Ciaran, when about to make his foundation at Clonmacnoise, set forth with eight companions from Hare Island, on Lough Ree; and, taking his way down the river, “rejected one spot as too fertile and too beautiful for the abode of saints”. Looking back through the mists of ages, we seem to see the little party of devoted men drifting along the quiet, sedge-bordered stream, where swallows dipped and darted as they do today; and every now and again a heron winged its solitary flight across that flat, yet flowing water, on either side of which stretch wide meadows that are often flooded, and that are called by the people callows.

Here, too, even at the present time, may be found that old and characteristic form of navigation — namely, the “cot,” or large flat-bottomed punt. Very picturesque indeed look those ancient craft when piled high with turf; and it is still no unusual occurrence to meet one being worked along the bank, with a pole from the stern, by a countryman in a large slouched hat, whilst a boy, on a thwart forward, keeps an oar out to the stream.

“The cot is indigenous,” says a well-known writer, — “as old, probably, as the skin-covered curragh”. Irish armies and Danish hosts, in all likelihood, used these curious boats; for history makes mention of no special difficulty experienced by the fleets in shooting rapids; though doubtless, when greater speed was required, they had “the long, narrow war canoes, which have been found time and again preserved in bogs.”

When the eight monks and their holy young leader arrived at the sloping field which was then named “The Height of the Spring,” Ciaran called a halt. “Here,” he cried, ” let us remain; for many souls will ascend to heaven from this spot !” Thus, in the year A.D. 544, on a site which eventually became so illustrious, was founded the venerable University of Clonmacnoise.

The monastic rule was exceedingly severe in those early days. Flesh-meat was almost excluded, and the small and zealous community lived, in very truth, the “simple life,” — building its own churches and cells of wood or wattles, spinning its own wool, farming its own land, whilst the religious were the inaugurators of whole societies of cooperative labour. The very end and object of their being was service; though, on the other hand, it is very evident that in a place where such scholars were produced, manual work must ever have been subservient to study. Scholars and teachers lived in small huts. “Classes,” we are told, “were held out of doors. Churches existed only for sacred uses; and they were multiplied, not increased in bulk, as the Congregation augmented.” Though there are seven of them still at Clonmacnoise, the largest is not more than sixty feet in length.

Some words of the Venerable Bede give us an excellent idea of this famous establishment, which has been quaintly described by a modern writer as “a germinal Oxford, reduced to its essentials, gown unallowed by town “. Writing of the great pestilence of 664, the saintly Benedictine historian tells us that “many of the nobility and the lower ranks of the English nation” were at that time in Ireland, which was also being devastated by the terrible sickness. Some, it seems, embraced the religious life; others chose to apply themselves to study, going about from one master to another. “The Irish,” he adds, “willingly received them all, and took care to supply them with food, also to furnish them with books and teaching gratis.” Here we have not only a vivid picture of the wandering scholars of those far-off days, but incontrovertible proof (furnished by one of the most remarkable Englishmen the world has ever known) of that charming Hibernian generosity and hospitality which still flourish as vigorously as of yore.

If we study its history with care, we find that the school of Clonmacnoise has contributed more to our knowledge of the past than almost any other seat of Irish learning. Foreigners, as has already been remarked, came to study within its venerable walls; and its inmates, though they had left the world and the things of the world, toiled and wrought and thought with an extraordinarily single-hearted devotion; striving by every means in their power, and in the face of difficulties which we, in the present age, can hardly realize, to raise their mental together with their spiritual standard. It has been truly said that they “had no desire to cloister their intelligences,” and the scholarly work they have left behind proves that such was indeed the case.

Colchu the Wise, who was the chief professor or lector (ferlegind), not only taught those who came from other countries to benefit by his training, but sent his own Irish pupils to study at the principal centres of learning abroad; for mention of them is made in a letter from “Alcuin, the humble levite, to his blessed master and kind father, Colchu”. This “humble levite,” as everyone knows, was one of the most gifted and influential men in Europe; and it is deeply interesting, after the lapse of many centuries, to read words that, from their intimacy, seem to bring the writer before us.

The whole tone of the letter makes it abundantly clear that the two scholars had met, even if Alcuin had not himself studied in Ireland, as some have believed. On the other hand, Colchu may have stayed in the celebrated monastery of St. Martin at Tours, when Alcuin presided over that favourite resort of Irish priests. However this may be, the two were friends— kindred souls — linked together by the strongest ties of affectionate sympathy; both had “followed knowledge like a sinking star beyond the utmost bounds of human thought”; and both had kept in constant touch, despite the changes that came with changing years.

“The news of your fatherhood’s health and prosperity rejoiced my very heart,” writes Alcuin; and he adds: “Because I judged you would be curious about my journey, as well as about recent political events, I have endeavoured to acquaint your wisdom with what I have seen and heard, so far as my unscholarly pen will permit me. First, let your loving care know that, through God’s mercy, the Holy Church has peace, and advances and increases in all quarters of Europe.” After further details of current happenings, he goes on: “For the rest, holy Father, let your revered self know that I, your son, and Joseph, your countryman, are, by God’s grace, in good health; and all your men who are with us serve God prosperously”. This last sentence refers, beyond a doubt, to Colchu’s pupils, and is in itself sufficient proof that they were then at Tours monastery.

At Clonmacnoise taught also, in 816, Abbot Suibhne (or Sweeny), whose fame was destined to live in the writings of his pupil Dicuil, an Irish monk who, in 825, wrote a geographical treatise “On the Measurement of the Globe,” which was discovered amongst the manuscript records in Paris, and which throws a very luminous light on those far-off days, and shows us “Irish monks making their way through Trajan’s Canal from Egypt to the Red Sea,” — men of science, as well as of religion, who considered it their duty to study those wonderful monuments of antiquity for which the mysterious land of Egypt is so famous. “Although we never read in any book,” writes Dicuil, “that any branch of the Nile flows into the Red Sea, yet Brother Fidelis told, in my presence, to my master Suibhne (to whom, under God, I owe whatever knowledge I possess), that certain clerics and laymen from Ireland, going to Jerusalem on pilgrimage, sailed up the Nile for a long way.” This same Brother Fidelis, Dicuil further informs us, “measured the base of a pyramid, and found it 400 feet in length”.

It is from Clonmacnoise that we derive the celebrated Book of the Dun Cow, which, with the exception of the Book of Armagh, is, says a reliable authority, “the most ancient compilation of which we have the original manuscript”. Maelmuire, the monk who copied it, was a scribe of note, and his end was most tragic. Robbers slew him in A.D. 1109, whilst he was writing in the great church; though in all probability he was working in a scriptorium, such as we may still see in Cormac’s chapel at Cashel, which is built over the church, under the high-pitched stone roof.

The great stone church which stands today was built by Flann, High King of Eire; and by Colman, then abbot both of Clonmacnoise and Clonard. Near this church is a wonderful sculptured cross, having, on its eastern side, scenes from the life of our Divine Lord; and, on the western, the interested archaeologist can still discern the Celtic inscription, now dim from the storms of centuries: “Pray for Flann, son of Malachy”. In another panel we read: “Colman made this cross for King Flann”. Firm and upright, it has braved the tempests of a thousand years, — a beautiful and touching type of that immutable faith so deeply rooted in Irish hearts that persecution, famine, poverty, and even death itself, have had no power to shake it.

Possibly earlier, but certainly not later, than the eleventh century, Ireland, we are told, “developed the art of vernacular literary prose, and the annalists had recourse to this medium of expression”. Some of the first of these, whose work has come down to us, lived and worked and died at Clonmacnoise. There, too, Duald MacFirbis made a copy of the annals of the Irish. This annalist, who was murdered by a Cromwellian soldier, was perhaps “the latest of all the hereditary professional scribes and scholars”.

Alas, for ruined Clonmacnoise, that ancient university within whose precincts lie so many illustrious dead! It will be remembered that Ciaran, when founding his abbey there, declared that many souls would ascend to heaven from that spot; and, as time went on, the conviction grew that those who were interred “in the graveyard of the noble Ciaran” would never, because the place was so hallowed, be condemned to eternal damnation. Royal personages deemed it an honour, and gave gifts in order that they might be buried there. Rory O’Conor, the last titular King of all Ireland, though he died in the Abbey of Cong, to which he had retired A.D. 1183, leaving his son as regent, yet found his last home at holy Clonmacnoise, whither his remains were carried, “to have St. Ciaran’s privilege”.

Long ages ago, Enoch O’Gillan wrote a poem about the dead at Clonmacnoise, which has been rendered into English. Two verses must suffice for quotation here: —

In a quiet watered land, a land of roses,

Stands St. Ciaran’s city fair,

And the warriors of Erin in their famous generations

Slumber there.

There beneath the dewy hillside sleep the noblest

Of the Clan of Conn;

Each below his stone, with name in branching ogham,

And the sacred knot thereon.

History shows that despite the fact that the celebrated seat of learning lay “pent between limitless bogs and the river” — far enough, it would seem, in its “passionless peace,” from the strife of tongues and the dreadful horrors of war, — it was, nevertheless, destroyed by violence some five and twenty separate times. Ten of these raids were carried out by the Danes, who plundered without mercy; the most famous of their leaders being Turgesius, whose aim appears to have been the complete conquest of Ireland. For the rest, Clonmacnoise, ruined, desolate, almost forgotten, it may be, offers many points of interest. And lovers of the past, who wander amongst its churches, towers, and crumbling walls, have no difficulty in repeopling it with grave, scholarly monks, and eager students athirst for knowledge; or in picturing the once warm welcome extended to all who sought learning and hospitality at their hands.

Marian Nesbitt, Our Lady in the Church and Other Essays (London, 1913), 216-224.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2025. All rights reserved.