January 17th is the feast of Saint Molaisse of Kilmolash, County Waterford. Like the other male saints with whom he shares his feast day, Ultán, Earnán and Clairnech, his name is also one shared by a number of saints. There are at least forty other saints called Molaisse found on the twelfth-century List of Homonymous Saints and thus trying to distinguish one from another is not an easy task. The most well-known bearers of this name are the patrons of Leighlin and Devenish and it is likely that some of the other saints Molaisse are doubles of this better-known duo. John O’Donovan, who was in the district of Kilmolash in June 1841 as part of his work for the Ordnance Survey, said of the parish ‘[Its name] is in Irish Cill Molaise, which signifies the church of St Molash, the celebrated saint of Devenish on Lough Erne’. It appears, therefore, that he believed Molaisse of Kilmolash to be the same person as Molaisse of Devenish. O’Donovan also recorded of the holy well that ‘Stations are still performed here but on no particular day, St Molaise’s being now forgotten’ (OS Letters, Waterford, p.133, 136).

Since not much can be confidently stated, Canon O’Hanlon takes refuge in poetry in the entry for Saint Molaisse in Volume I of his Lives of the Irish Saints:

Article VI. St. Molaisse, of Cill-Molaisi, now Kilmolash, County of Waterford.

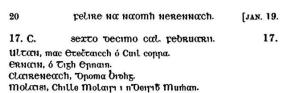

A festival in honor of Molaisse, of Cill-Molaisse, is entered in the Martyrology of Tallagh, at the 17th of January. From the following notice, this place should be sought for in the Decies of Munster; for on this day, Molaisi, of Cill-Molaisi, in Deisi-Mumhan, is recorded in the Martyrology of Donegal. We find the exact place, in the present denomination of Kilmolash parish, partly in the barony of Decies-within-Drum, but chiefly in that of Decies-without-Drum, in the county of Waterford. The ruins of religious edifices may yet be seen within this parish, and on a townland bearing a like name. Although the time when this present saint flourished has escaped detection, yet of his place the truant imagination depicts in the times of old

” various goodly-visaged men and youths resorting there,Some by the flood-side lonely walked; and other some were seen

Who rapt apart in silent thought paced each his several green;And stretched in dell and dark ravine, were some that lay supine,

And some in posture prone that lay, and conn’d the written line.”[“Congal” by Sir Samuel Ferguson, Book i, lines 18-22.]

Rev. John O’Hanlon, Lives of the Irish Saints, Volume I (Dublin, 1875?), p.299.

Diocese historian, Canon Patrick Power, mentioned a holy well less than a mile from Kilmolash but attributed its dedication to Saint Colum Cille, whilst noting that a well which once adjoined the church was now lost:

Proceeding along the bank of the Finisk in a south-easterly direction for about a mile, we come to Kilmolash Bridge, adjoining which stand the ruins of a very ancient church, known as Kilmolash Church. It stands in the centre of an enclosed graveyard, on a higher level than the road, which passes within a few yards of it, and its evident antiquity adds considerably to the interest of the locality, which is extremely picturesque. The townland is situated in the electoral division of Whitechurch, and it is also a parish in the Dungarvan Union. I have been informed by several old people of the place that a holy well exists in a field adjoining the church, but that it was covered in many years ago, and now no trace of it can be found.

It is stated by the Bollandists that the Danes plundered Kilmolash.

As it is recorded that in the years 912, 913, and 915 Dungarvan and Lismore were plundered by these marauders, in fact that the greatest part of Munster was wasted by them and the booty taken to Waterford, in all probability Kilmolash suffered from them on their march from Dungarvan to Lismore.About half-a-mile distant from Kilmolash Church may be seen the Holy Well of St. Columbkille. It is situated in Curraghroche Wood, in a very secluded spot, and surrounded by fine specimens of oak trees. The people of the district hold this well in great veneration, and sick and afflicted people are often brought there in the pious belief that the great saintwill restore them to health. When and under what circumstances St. Columbkille visited this locality I have no record to show, but perhaps some of the many readers of the Journal may be able to point out.

Rev. P. Power, ‘Ancient Ruined Churches of Co. Waterford’, Journal of the Waterford & South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society, (1894-95), Volume 1, 155-56.