On May 14 we commemorate Saint Carthage (Mochuda) of Lismore, County Waterford. I have previously posted an introduction to his life by Father John Ryan S.J. here, but below is a paper by a resident of Lismore, W.H. Grattan Flood (1857-1928), a prolific contributor to the antiquarian and religious periodicals of his day. Flood published an entire ecclesiastical history of Lismore in the Journal of the Waterford and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society, of which this paper forms a part. In the extract below, the author gives a retelling of the traditional account of Saint Carthage and his expulsion from the Abbey of Rahan:

ST CARTHAGE OF LISMORE.

By WILLIAM H. GRATTAN FLOOD.

The early years of the seventh century found Christianity fairly well established in the territory of Nan Desie. Already the monasteries of Ardmore, Molana, Dungarvan, Ballintemple, Mothel, etc., were famous, and sent forth numerous disciples to take up the good work of St. Declan. As yet the city of Waterford was unknown, and so was Lismore. But the Providence of God was mysteriously working, and a great servant of God was already qualifying to be sent as the Apostle of Magh-Sciath. In a previous number of the Journal I explained the entry under date of 634, recording the death of “Eochaid, Abbot of Lismore,” which has reference to Lismore in Scotland.

About the year 614 St. Carthage, Abbot of Rahan, visited Kerry Currihy and was royally entertained by Carbery Criffan, King of Munster. Whilst still in this part of the country a very dreadful incident occurred. The Queen and her son, Aidus (Hugh) were killed by a thunderbolt, and the monarch, plunged in grief, besought the saint to make intercession to God on their behalf, whereupon the mother and son were restored to life. (a) No wonder that the king was profuse in his thanks for such a miracle, and he bestowed most signal marks of favour on St. Carthage, “to enable him to extend his great work.”

Finghin, son of Hugh Dubh, King of Munster, died in 621, but his wife, Mor, lived until the year 632. The new ruler of Munster, Cathal MacHugh, was not only blind, but was also a deaf mute, and as such was incapable of being sovereign. His courtiers bethought of St. Carthage, to whom they sent a most urgent message on behalf of the invalid king, and the saintly Abbot of Rahan again journeyed southwards. In the quaint language of the Life: “Mochuda came where the king was, and the king and his friends implored Mochuda to relieve his distress. Mochuda made prayers to God for him, and put the sign of the holy cross on his eyes, and ears, and mouth, and he was cured of all his diseases and troubles, and the King Cathal (b) gave extensive lands to God, and to Mochuda, for ever, namely, Cathel Island, and Ross Beg, and Ross Mor, and Pick Island; and Mochucla sent holy brethern to build a church in Ross Beg in honour of God, and Mochuda himself commenced building a monastery in Pick Island, and he remained there a full year.” According to the Life, St. Carthage placed three favourite disciples in Cathel Island, Ross Beg, and Ross Mor, viz: “the three sons of Nascann, i.e. Bishop Caban [Gobban], and Straphan [Stephen] the priest, and Laisren [Molaise] the saint.

In 628 St. Carthage was still only an Abbot, and on that account he requested the holy Bishop of Ardmore [St, Domaingen] to ordain and bless as Abbots the three above-mentioned disciples, in his own presence.” The modern reader will need to be informed that these three abbeys were in Co. Cork, not far from Ardmore, but were afterwards incorporated with the diocese of Cloyne- Pick Island in particular, although unidentified by some Irish writers (including the great O’Donovan), is best known as Spike Island, near Queenstown, of which St. Ruissen was first Abbot, and which twelve centuries later was used as a convict depot. St. Carthage appointed the Bishop of the Nan Desie, to have spiritual jurisdiction over the three abbeys, “and he left two score more of his brethren in his own stead in the monastery of Pick Island.”

“Mochuda then returned towards Rahan. On his way eastward through Munster he passed over a river which was called Nemh at that time, but which is called Abhan Mor to-day, and he saw a large apple in the middle of the ford over which he was passing, and he took it up and carried it in his hand, and hence Ath-Abhal (or Aghowle, now Appleford) in Fermoy, has its name.

And the servant asked for the apple from Mochuda, and he did not give it, but said: ‘God will work a miracle with this apple through me this day, for we shall meet the daughter of Cuana MacCailchen, with her right arm powerless and motionless, hanging by her side, and she shall be cured through this apple, and through the power of God.’

“And this was verified; for Mochuda saw the virgin with her maiden companions at their sports and amusements on the green of the court, and going up towards her he said: ‘Take this apple to thyself, my daughter.’ She stretched forth her left hand for the apple, as was her wont, but Mochuda said: ‘Thou shalt not get it in that hand, but reach out the other hand for it, and thou shalt get it.’ And the maiden, being full of faith, attempted to reach forth the right hand, and the hand was instantly filled with vigour and life and she raised it out and took the apple into it.

“There was joy all over the king’s palace on this occasion, and all gave praise to God and to Mochuda for this miracle. And Cuana said on that night to his daughter: ‘Make now your selection, and say whom you like best of all the princes of Munster, and I will have him married to you.’ To this the maiden replied: ‘I will have no husband but the man who cured my hand,’ ‘Hear you that, O Mochuda,’ said Cuana. ‘Give me the maiden’ said Mochuda, ‘and I will give her as a spouse to Christ, Who cured her hand.’ And Cuana gave the maiden and her dowry, with an offering of land on the bank of the river Nemh [Blackwater] to God and to Mochuda for ever; and his munificence was too great to be described.

“Flandath [or Flaithniath, identical with Flanna] was the maiden’s name, and Mochuda brought her with him to Rahan, where she spent her life most profitably with the other ‘Black Nuns’ till Mochuda was banished by the King of Tara out of his own city, when he took Flandath with him, and the rest of the Black Nuns.”

About five years after the return of St. Carthage to Rahan, namely, during the Easter-tide of the year 635 (O.S. 634), a wicked prince called Blathmac expelled the saint and his monks from the monastery which had shed such blessings around the country for forty years. However, this apparently terrible misfortune led to the happiest results because it eventuated in the foundation of the great Abbey and University of Lismore.

St. Carthage and about five hundred of his monks (exclusive of conversi and lepers), journeying through Drumcullen (near Birr), Saigher, and Roscrea, came to Cashel, where they were welcomed by Falvey Flann, King of Munster. At that time it so happened that Maelctride, son of Cobhthaich or Coffey, Prince of the Desie, was on a visit with his royal father-in-law, and he unconsciously co-operated in the design of God by offering the future patron of the See of Lismore a large tract of land in his country whereon to build a monastic establishment. The saint gladly accepted the offer, and viewed it as a distinct revelation from on high. The monks then proceeded via Athassel, Ardfinnan, Clogheen, Affane and Cappoquin, (c) and halted within three miles of the present town of Lismore, in a townland near Ballysaggartmore, ever since known as See Mochuda, “the seat of St. Mochuda,” where a holy well sprang up at the bidding of our saint. (d)

On approaching Magh Sciath the progress of the monks was impeded by the Aw Mor, or Broad Water, which was then at flood tide. There being no boats available, St. Mochuda commanded two of his favourite disciples, SS. Molna and Colman, to join their prayers with his, and that perhaps it would please Heaven to work a miracle. Almost immediately, as we read in the Life, the swollen waters of the dark rolling river were parted, and a perfectly dry passage was opened to the exiled community. Thus, in the summer of the year 635, St. Carthage settled at Magh Sciath, in a tract called Dun Sginne, i.e. “the fortress of the flight,” commemorative of the expulsion from Rahan. He endured much since leaving his beloved monastery in King’s Co. (then portion of Co. Meath), and was very sad thereat. St. Cuimin of Connor thus sings of him:-

“The beloved Mochuda of Mortification;

Admirable every page of his history.

Before his time there was no one who shed

Half so many tears as he shed.”

The Irish Life tells us that, having viewed the site of his new foundation, (e) St. Mochuda cried out: ” Here shall be my rest, for I have chosen it.” He at once began to build a circular enclosure on Dun Sginne, now known as the “Round Hill,” and busied himself unceasingly in directing the monks in their operations. The Life goes on to state that a certain holy virgin named Cornelia or Caemghill, who inhabited a small cell in the neighbourhood, likely adjoining Temple Declan at Drumroe, approached the new-comers and enquired the nature of their work. “We are building a small Lis here” said St. Mochuda. “A small Lis [Lis-beg]!” said the woman: “this is not a small Lis, but a great Lis [Lis-mor],” said she, “and so,” we are told, “that church ever since continued to be called by that name.”

To the above incident is due the present name of Lismore. Lios-Mor is justly equated as the great Lis or the great Rath –the words Lis and Rath being practically the same, and Lismore, which is rendered in the Latin Life as Atrium Magnum, means the “great entrenchment of earth.” Near Lismore there is a very extensive townland still called Rath (pronounced as if written Ralph), divided into Upper and Lower Rath. Thus was founded Lismore, generally translated ” the great habitation; ” and the pagan Magh Sciath, or Campus Scuti -the plain of the shield-a plain of solid limestone formation-disappears from history. Traces of the ancient double trench are still to be seen near Deerpark.

The Life continues:- “And when he had finished his own city of Lismore he sent Flandath [the Nun from Fermoy, previously mentioned] to her own country, that she might build a church there. And she built a noble church in Cluain Dullain [Clondulane, about eleven miles from Lismore, near Fermoy], and it is in Mochuda’s parish [diocese] it is,” For the sake of chronological sequence I shall here add that this holy Abbess was joyfully received, by her father, Cuan MacCailchen, and laboured for many years in Clondulane. (f) This Cuana, Prince of Fermoy, was also called Laech Liathmhuine, i.e. “the hero of Liathmhuin,” afterwards known as Clogh-lemon. He died in 642.

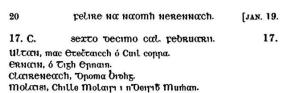

St. Carthage lived scarcely two years after the foundation of the Abbey and Cathedral. Finding his end approaching he retired to a lonely valley at the east end of the town, near the present St. Carthage’s Well (in the garden of Mr. Maurice Healy), where he spent over a year in contemplation and prayer. At last he summoned his monks and gave them a farewell exhortation and blessing. “After this, being favoured with a vision of angels, he asked to receive the Body and Blood of our Lord, and then departed in peace.” His pure soul was seen, according to the oft-quoted Life, ascending into Heaven “on the day before the Ides of May,” and thus passed away the first Abbot-Bishop and founder of the See of Lismore, on May 14th, 637, the feast of his natale. (g)

In the ancient Irish Office of St, Carthage, the following beautiful Antiphon was sung at the Magnificat:-

“Gloriose Praesul Christi, venerande Carthage,

Apud Deum tuo sancto nos juva precamine,

Ut detersa omni sorde, et abluti crimine

In coelesti sempiternum collaetemur culmine.”

Colgan tells us that the rule (h) of St, Carthage was almost similar to that of the reformed Cistercians, or to the order of La Trappe, of which there are two well-known Abbeys in Ireland. “When any of the brethren returned from a mission, it was the rule to kneel down before the Abbot, and, in that humble posture, relate the events which had occurred. All kinds of austerities were here practised, and the monks lived by their labour, and on the vegetables which they cultivated with their own hands.” The order was afterwards incorporated with the Regular Canons of St. Augustine-an order which must not be confounded with the Hermits of St. Augustine or the Austin Friars.

Allemande, in his Monastic History of Ireland, published at Paris in 1690, thus writes from the ancient Life:-“Lismore is a famous and holy city, into the half of which, in consequence of being strictly cloistered, no woman dare enter. It is filled with cells and holy abodes of prayer, and a number of pious men are always in it. Religious men flow to it from every part of Ireland, England, and Britain, being desirous to remove to Christ; and the city itself is situated on the banks of the river formerly called Nemh, lately called Abhan Mor, that is, the Great River, in the territory of Nan Desie.”

In the Litany of Aengus the Culdee, dating from 798, we find that ancient hagiologist invoking “eight hundred monks who settled in Lismore with Mochuda, every third of them a favoured servant of God.” He also invokes “the seven bishops of Donough-Youghal”, the “seven bishops of Donoughmore Magh Feimhin” etc. In a very ancient catalogue of the principal monasteries in Ireland, cited by the learned Dr. O’Conor, and also by Hardiman, Lismore is entitled “the Litanies of Ireland.”

The number of disciples who gathered round St. Carthage before his death is variously estimated. Some authorities give the number as over a thousand, whilst the ancient lives vary from 844 to 867 monks. Professor Hogan writes:-” Lismore had no spacious halls, no classic colonnades, no statues, or fountains, or stately temples. Its houses of residence were of the simplest and most primitive description, and its halls were in keeping with these mere wooden structures, intended only to shut off the elements, but without any claim or pretence to artistic design. And yet Lismore had something more valuable than the attractions of either architecture or luxury. It possessed that which has ever proved the magnet of the philosopher and the theologian-truth, namely, and truth illumined by the halo of religion. It sheltered also in its humble halls whatever knowledge remained in a barbarous age of those rules of art that had already shed lustre on Greece and Rome, or had been fostered in Ireland itself, according to principles and a system of native conception.” St. Colman (previously alluded to) was one of the principal professors of the infant university, under whom studied the youthful St. Flannan, the subsequent founder of the See of Killaloe.

Archbishop Usher had two manuscript copies of the Irish Life of St. Carthage, and Smith, in his history of Waterford, says that one of these Lives begins “Gloriosus Christi miles.” In 1634 Philip O’Sullivan Beare sent the Latin translation of the “Irish Life of St. Mochuda” to Father John Bollandus, S.J. It is much to be deplored that we have not an accurately edited English version of the Irish Life. (i)

Maeloctraigh, Moelctride, or Mael MacTirid, Prince of the Desie, died early in 637, some months previous to the death of St. Carthage. It is probable that he was buried in Lismore, and he was succeeded in his kingship by Bran Fionn, or Bran the Fair, son of Maeltricle, who proved a munificent benefactor to the Cathedral of Lismore, which was a Damlaig or Stone Church. It is only to our present purpose to add that Nualathan, the aged widow of Prince Maeloctraighe, died in 670.

To the archaeologist, one of the most interesting facts in regard to the history of St. Carthage is the identification of the sites connected with his ministry. Many distinguished writers, including Cardinal Moran and Bishop Healy, have asserted that the name of St. Carthage, or yet the memory of his labours, has not been much in evidence in the topography of the county. On the contrary, his name is “writ large” in the district around Lismore, as an intimate knowledge of the local topography will amply testify. His Cathedral and Well have been already alluded to, as also See Mochuda, near Ballysaggartmore, and Rath Upper and Lower. I am glad to be able to identify the old monastic cemetery, as, alas! the present generation scarcely knows its name. This is none other than the field on the left hand side of the avenue leading to Lismore Castle, and known to the older inhabitants as “the relic.” The Celtic name is relig or “churchyard,” and when some operations were going on in connection with the town drainage in 1891, in the spot now called the “New Walk” (although nearly a century old), numerous bones were disinterred, (j) especially outside the gateway leading to Lisrnore Villa.

Not far from the present Cathedral, adjoining Ballyneligan Glebe, is one of the sites of the hermit cells of Lismore. From the 7th to the 12th century we meet with many entries in the Irish Annals referring to the “Anchorites” of Lismore; and one of the termon lands which they became possessed of in after days was known as the “Anchorites’ Land,” now called Ballinanchor. The site referred to is Cumaillister, the valley of the cliff hermitage, ister being a corruption of disert, originally meaning a desert, but afterwards frequently, applied to churches and hermitages in solitary places.

The Sarughadh, pronounced Scorroogh, about half a mile from Lismore, and marked on the Ordfiance Map as ” Ballysaggartbeg: Wood”, was a sanctuary land from the 7th century, whilst adjoining it is Ballinaspick, or Bishopstown. The names Ballysaggart = the priest’s townland, Burgessanchor, Baldydecane, Aglish (near Castlerichard), Glensaggart, Tubrid, Monataggart, Tubber-na-hulla, Boher-na-neav, etc., suggests at once the religious life of the locality.

In other portions of the Desie country the name of St. Carthage survives in Kilcaragh, near Killure, Temple Carthaig, and Cloghcuddy; whilst in Co. Cork we meet with Coolemogillacuddy and Garranmocuddy; and in Co, Wexford, Coolnacuddy. (k)

By a truly marvellous dispensation of Providence,(almost exactly as happened to St. Carthage when he was expelled from Rahan), we, in our own day, behold the successors of another exiled community, driven from France in 1831, silently toiling and praying on the side of Knockmealdown mountain, six miles from Lismore. The rugged barrenness of the “ bare brown hill” has become a smiling garden, thoroughly accentuating its honeyed name of Mount Melleray; and the present writer recalls vividly his boyish feelings at the interment of the last of the pioneer Trappists-Brother Similien -a French monk, who ended his days, almost a centenarian, in that grand Abbey which fittingly represents in this degenerate age the primitive wattle cells and pure faith of the glorious St. Carthage of Lismore.

Notes

(a) Irish Life of St. Carthage

(b) King Cathal died in 625, or, according to some, in 630.

(c) Whilst in the neighbourhood of Cappoquin St. Carthage and his companions halted at a cell called Killcluthair, now Englished Kilcloher, and for three days and three nights were hospitably entertained by the Abbot, St. Mochua, Miannain, who presented the cell to St. Carthage. Kilcloher means “the churchof the shelter,” and is four miles east of Cappoquin.(Dr. Joyce).

(d) Seemochuda is a natural seat, somewhat like an arm-chair of “primitive man ;” and the well is close at hand, which, by a constant tradition, is said to have come into existence at the command of St. Mochuda by merely planting his crozier there.

(e) In the ancient Irish Life we read that St. Columbkille had predicted the foundation of Lismore on the occasion of a visit to St. Carthage at Rahan:-

“Formerly from the top of Slieve Cua, thou hast seen a great band of angels on the bank of the river Nemh, and raising to Heaven a silver cathedral with a golden image in it. There shall be the place of thy resurrectidn. That church of silver is thine, and the golden statue placed in it represents thee.” It is strange that Ussher, Archdall, and Lanigan located Rahan as “Rathyne, in the barony of Tertullagh, Co. Westmeath,” but certain it is that the site of St. Carthage’s foundation was Rahan, in the barony of Eglish, near Tullamore-not far from Tullabeg.

(f) There is a townland formerly known as Ballymacpatrick in the parish of Clondulane, now called Careysville. Strangely enough Canon O’Hanlon was unable to identify Clondulane.

(g) According to the prophecy of St. Colman Elo, the Reilig, or cemetery of St. Mochuda, “designated by the angels, was that in which our saint was buried “-afterwards known as-” the cemetery of the Bishops.” St. Ita also foretold the fame of St. Mochuda’s cemetery, where, subsequently innumerable servants of God were laid at rest,

(h) There were thirteen different monastic Rules in the early Irish Church, namely, those of SS. Ailbe, Declan, Patrick, Bridget, Columbkille, Carthage, Molua,, Mochta, Finian, Columbanus, Kieran, Brendan, and Comgall.

(i) Among the valuable MSS. of O’Curry, now housed in Holy Cross College, Clonliffe, there are two lives of St. Carthage. One of these is a transcript of the ancient Irish Life, whilst the other is a translation from the Irish. The Salamancan “Life” is in the Burgundian Library at Brussels, but the Vita Secunda is the one usually quoted.

(j) On April 26th, 1897, two papers were read before the Royal Irish Academy on the subject of those remains, but no definite conclusions were arrived at.

(k) The present name of this townland is Courtnacuddy, but the Irish speaking and old residents still call it Cuil-ne-cuddy = the recess of St. Cuddy, ne being an old Celtic endearing term similar to mo-as is seen in the place name Ardnekevan. In 16th century records it is written Courtmocuddy. From the Irish Life we learn that “a large tract of land near Ardfinnan, Co.Tipperary, was afterwards formed into a parish, dedicated to St. Mochuda.

Journal of the Waterford and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society, Volume IV (1898), 228-237.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2018. All rights reserved.