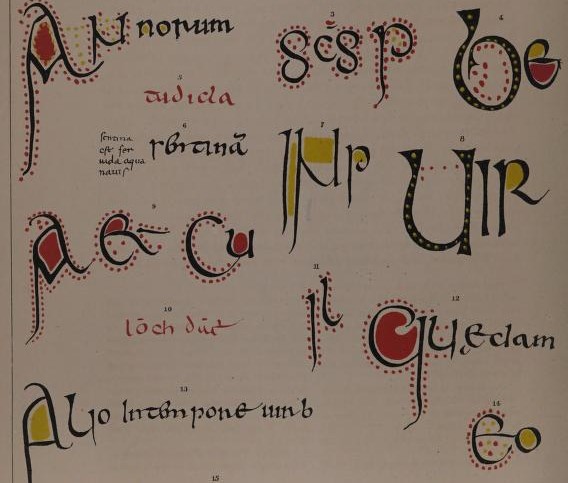

Marking International Women’s Day with The Litany of the Virgins, a lorica-type prayer which invokes the protection of twenty-eight Irish women medieval saints. Among them are the four female saints with written Lives – Brigid, Íte, Moninne and Samthann. I note that Our Lady, the Holy Virgin of Virgins, heads the list followed by her Irish equivalent, Saint Brigid, the Mary of the Gael. This Litany is number eleven in the collection Irish Litanies published by the Rev. Charles Plummer a century ago. The original was preserved in the twelfth-century Book of Leinster. Below is the Irish text followed by Plummer’s translation.

Litany of the Virgins

[1] [No]m churim ar commairge

Maire ogi ingini,

Brigti báne bruthmaire,

Cua[che] mor-glaine,

Moninni is Midnatan,

Scire, Sinchi, Samchaine,

Caite, Cuacae, Coemilli,

[C]raine, Coppe, Cocnatan,

Nessi ane Ernaigthi,

Derbfhalen is Becnatan,

Ceire is Chrone, is Chailainne

Lasrae, Lochae, is Luathrinni,

Ruind, Ronnait, [R]ignaige,

Sarnat, Segnat, Sodeilbe,

Is na nóg i noen-baile,

Tuaid, tess, tair, tiar.

[2} Nom churim ar commairgi

Na Trinoite togaide,

Na fádi, na fir-apstal,

Na mmanach, na mmartirech,

Na fedb is na foismidech,

Na nog is na nirisech,

Na noem is na noem-aingel,

Ar cach nolc dom anacul,

Ar demnaib, ar droch-doenib,

Ar dornom, ar droch-aimsir,

Ar galar, ar gu-belaib,

Ar uacht is ar accorus,

Ar anaeb, ar escuni,

Ar dígail, ar dairmitin,

Ar dinsem, ar dercháine,

Ar mi-rath, ar merugud,

Ar theidm bratha borrfadaig,

Ar olc iffirn il-phiastaig

Co nilur a phian.

Translation

I place myself under the protection

Of Mary the Pure Virgin

Of Brigit, bright and glowing,

Of Cúach of great purity,

Of Mo-ninne and Midnat,

Of Scíre, Sinche and Samthann,

Of Caite, Cúach and Coímell,

Of Craine, Cop and Cocnat,

Of Ness the glorious of Ernaide,

Of Derfáilind and Becnat,

Of Ciar and Cróine and Coílfhind,

Of Lasair, Lóch and Luaithrinn,

Of Ronn, Rónnat, and Rígnach,

Of Sarnat, Segnat, and Soidelb,

And of the Virgins all together

North, South, East, West.

I place myself under the protection

Of the excellent Trinity,

Of the prophets, of the true apostles,

Of the monks, of the martyrs,

Of the widows, and the confessors,

Of the virgins, of the faithful,

Of the saints and the holy angels;

To protect me against every ill,

Against demons and evil men,

Against thunder (?)and bad weather,

Against sickness and false lips,

Against cold and hunger,

Against distress and dishonour,

Against contempt and despair,

Against misfortune and wandering,

Against the plague of the tempestuous doom,

Against the evil of hell with its many monsters.

And its multitude of torments.

Rev. C. Plummer, ed. and trans., Irish Litanies: text and translation. Edited from the manuscripts. (Henry Bradshaw Society, London, 1925)92-3; 121-3.