The holy valiant deeds

Of sacred fathers.

Based on the matchless

Church of Bangor;

The noble deeds of abbots,

Their number, times, and names,

Of never-ending lustre—

Hear, brothers, great their desert,

Whom the Lord hath gathered

To the mansions of His heavenly kingdom.

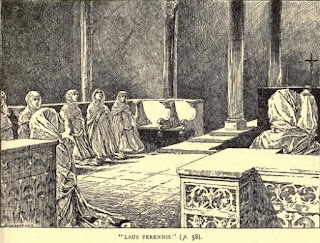

Thus does the hymn ‘Commemoration of our Abbots’, preserved in the Bangor Antiphonary begin. August 1 is the feast day of one of those abbots, Sárán, who exercised his authority over the monastery at Bangor, County Down in the eighth century. Bangor, famous for its tradition of laus perennis (unceasing praise), was founded in the mid-sixth century by Saint Comgall. This spiritual and intellectual powerhouse produced a number of important saints including Saint Columbanus and the famous reckoner of the computus, Mo-Sinnu (Sillán), hailed as the ‘renowned teacher of the world’ in the hymn in praise of the abbots. In his entry for today’s saint below, taken from Volume VIII of his Lives of the Irish Saints, Canon O’Hanlon brings us the evidence from the calendars and annals which date Abbot Sárán’s career. He also mentions an 1871 paper in an antiquarian journal whose author tries to link our Bangor abbot to the County Louth townland of Kilsaran. I looked at this reference for myself and the author does indeed simply assert that ‘The parochial name Kilsaran, Cill-Saran, recalls S. Saran, Abbot of Beannchair, Co Down, whose death is recorded by the “Four Masters”, A.D. 742’. However, the Bangor abbot is but one of a number of Irish saints who bear this name and there is no reason to automatically assume that he must be the one who lent his name to the Louth parish:

Article III. St. Saran, Abbot of Bangor, County of Down.

[Eighth Century.]

In former times, it is probable, that the acts of many native saints were preserved; although, for want of some fostering care, those records have long since sunk into oblivion. A festival to honour Saran, Abbot of Bennchor, was celebrated at this date, as we find recorded in the Martyrology of Tallagh. Several Sarans are mentioned in our Calendars, and at different dates. Of the early history of the present Saran, no record seems to be extant; but, we may fairly infer, that he belonged to the religious community of the Bangor monks, whose abbot St. Flann of Antrim departed this life, A.D., 722. It is probable, that Saran was appointed his immediate successor. Referring to the present saint, Major-General J. H. Lefroy appears to derive the parochial name of Kilsaran, in the Barony of Ferrard, and County of Louth, from this holy Abbot of Bangor; but, on what grounds, we do not find stated. The death of Saran, abbot of Bangor, occurred, in the year of our Lord 742. His feast occurs at this date, likewise, in the Martyrology of Donegal.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2022. All rights reserved.