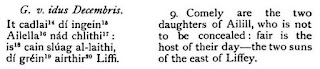

There is a rather intriguing saint who occupies the entire entry of the Martyrology of Oengus for December 8:

8. The triumph of humble Egbert,

who came over the great sea:

unto Christ he sang a prayer

in a hideless coracle.

The scholiast has noted:

8. Ichtbrichtan, i.e. from Diln Geimin in Ciannachta of Glenn Geimin, or in Mayo of the Saxons, in the west of Connaught. Or in Connaught, i.e. in Mayo of the Saxons in Cera. Vel in alio loco diuersi diuerse sentiunt. Or of Tulach leis of the Saxons in Munster, and Bercert is his name. Or Icht-ber etc., i.e. Ichtbricht who is in Tech Saxan (‘the House of the Saxons’) in Hui Echach of Munster, and he is a brother of Benedict of Tulach leis of the Saxons. And a brother of theirs is Cuithbrecht, and in the east [i.e. in Britain] he remained.

‘Mayo of the Saxons’ is inextricably linked to the Paschal Dating Controversy, as following the adoption of the Roman method of calculating the date of Easter at the Synod of Whitby in 664, Saint Colman of Lindisfarne led a group of monastics unwilling to accept the new practice back to the west of Ireland. Saint Colman founded a monastery on the Island of Inisboffin where he and his brethern, which included a number of Saxon monks, could continue with the Irish practices but tensions arose and eventually a separate foundation was made on the mainland. This was known as Mágh nEó na Saxan or Mayo of the Saxons. Mayo of the Saxons developed quite a reputation as a monastic school under the leadership of Saint Gerald and continued to attract English students.

As we have seen from the scholiast’s notes above though, there is some uncertainty as to where exactly our saint Ecbrit or Egbert fits into the picture. His memory was certainly passed on, for the Martyrology of Marianus O’Gorman also records ‘Ecbyrht’ on this day and the Martyrology of Donegal has a note on ‘ECBRIT, or Icbrit. Marianus. He seems English’ added by a later hand. The earlier scholiast raised the possibility that this Saint Ecbrit may be related to Berechert of Tullylease, who is commemorated on December 6. In my post on Saint Berechert, whose identity is equally problematic, there was mention of a tradition that he was one of three Saxon brothers. The translator of the Martyrology of Oengus, Whitley Stokes, however, raises another possibility in his index to the work:

Ichtbrichtan, Dec. 8, pp. 256, 258, probably the Northumbrian Egcberct who persuaded the community of Hi to adopt, the catholic Easter and the coronal tonsure, Baeda H.E. III. 4, v. 9, 22, Reeves Col. 379.

Now this Northumbrian saint does have a distinct identity recorded in the sources. Below is an account of him from Archbishop John Healy’s work on the monastic schools of Ireland:

Another eminent saint and scholar of foreign origin .. was Egbert of Northumbria. Bede gives a very interesting account of this eminent man. He was sprung from the nobility of Northumbria, and appears to have been born in A.D. 639.

With another young noble named Ethelun, Egbert went over to Ireland, like the crowds of his countrymen, ‘to pursue divine studies, and lead a continent life.’ They sojourned in the monastery, called in Irish Rathmelsigi… Colgan says that this monastery of Rathmelsigi was in Connaught ; but he does not specify, and probably did not know, the exact locality. In the Martyrology of Donegal, we find reference to “Colman Rath-Maoilsidhe ” (at Dec. 14th ) which is in all probability the monastery referred to by Colgan. This Colman is different from Colman of Innisbofin, whose festival day is the 8th of August. It is not improbable that his monastery was situated at the place called Rath-maoil, or Rath-Maoilcath, both of which were situated near Ballina, on the right bank of the Moy. Everything points to the fact that most of the young Northumbrian nobles and ceorls, who came to the West of Ireland in crowds at this period, landed in the estuary of the Moy, and then going southward, took up their abode, or founded their religious houses wherever they could obtain suitable accommodation. St. Gerald’s Abbey of Mayo was not then established (in a.d. 664) ; and so Egbert and his companions put themselves under the guidance of St. Colman, or some of his successors, in this monastery of Rath-Maoilsidhe.

Just then the terrible Yellow Plague made its appearance in Ireland, and carries off one-half of its population. All the companions of Egbert and Ethelun were cut off by the plague ; and now they themselves were attacked, and became grievously ill. Then Egbert, whilst he had yet a little strength remaining, rose up in the morning, and going out of the chamber of the sick, he sat down alone, and began to think of his past sins ; and he asked God’s pardon for them with many tears. He prayed, too, earnestly that God would not yet take him out of the world, but would give him time to atone by his good works for the sins of his youth. And if God deigned to hear his prayer, he vowed never to return again to his native Britain, but to live as a pilgrim in some strange land ; and, moreover, to recite the Psalter dailv, and to fast continuously for twenty-four hours once a week. When he returned to the sick chamber, Ethelun, his companion, was asleep ; but presently awaking, he told Egbert that his prayer was heard by God ; then he gently rebuked him, for he had hoped that together they would go into life everlasting. Next day Ethelun died ; but Egbert recovered from his sore sickness, and lived to be ninety years of age, when he departed from this life.

He was ordained a priest; “and his life,” says Bede,”adorned the priesthood, for he lived in the practice of humility, meekness, continence, justice, and all other virtues.”He loved the Irish greatly, and lived amongst them for fifty years (a.d. 664-715), preaching the Gospel, teaching in his monastery, reproving the bad, and encouraging the good by the bright example of his blameless life. He not only kept his vow, but he added to it, says Bede ; for during the whole Lent he took but one meal in the day, and that was nothing but bread in limited quantity, and thin milk from which the cream had been skimmed off. Whatever he got from others—and he got much—he gave to the poor.

For many years he had been resolving in his mind to sail round Britain, and go to Germany to preach the Gospel to the pagan tribes who dwelt there, and who were kindred to his own nation of the Angles. But God had willed otherwise. There was in Egbert’s monastery an old monk who had many years before been minister to Boisil, Abbot of Melrose, an Irish foundation in Scotland. Now one morning after matins, Boisil appeared to this aged monk, who at once recognised his old master, and commanded him to tell Egbert that it was God’s will that he should give up his proposed journey to Germany, and go rather to instruct the Columbian monasteries in the right method of keeping Easter, and of tonsuring the head.

Egbert fearing that this vision might be a delusion, still continued his preparations for Germany, and did not obey the direction given by Boisil. Then that saint appeared for a second time to his minister, and commanded him to make known to Egbert, in a more imperative way, what it was God willed him to do. ” Let him go at once,” he said, ” to Columba’s monastery of Hy, because their ploughs do not go straight, and he will bring them into the right way.” Moreover, the ship in which he was preparing to set out for Germany was wrecked in a storm, and thrown upon the shore, leaving, however, his effects intact. Egbert, taking this as a further manifestation of the Divine will, gave up his project of going to Germany, and set sail for Iona. Wictbert, however, one of his associates in religion in Ireland, went in his stead, and for two years preached the Gospel in Friesland, but reaped no harvest of success amongst the pagans. So he returned once again to Ireland, and gave himself up to serve God during the rest of his life, as he was wont to do before his departure, in great purity and austerity; “so that if he could not be profitable to others by teaching them the faith, he took care to be useful to his own beloved (Irish) people by the example of his virtues.”

Now when this holy father and priest, Egbert, beloved of God, and worthy to be named with all honour, came to the monastery of Iona, he was honourably and joyfully received by the community. He was also a diligent teacher, and carried out his precepts by his example, so that he was willingly listened to by all the members of the community. The effect of his frequent instructions and pious exhortations, was that at length the community of Hy consented to give up the inveterate tradition of their ancestors in religion, and adopt the new discipline, which by this time had been received everywhere else throughout the Irish Church. Now surely, this was, as Bede observes, a wonderful dispensation of Providence, that these very monks of Iona, who were the first to preach the Gospel in Northumbria, should afterwards be persuaded by this Northumbrian priest to accept the correct discipline and true rule of spiritual life. And stranger still, it was on Easter Day, the 24th of April, a.d. 729, that this man of God went to his eternal rest ; whereas, but for his exertions, that Easter festival would not have been duly celebrated on that day, but, in accordance with the unreformed system, would have been celebrated in that year towards the end of March, whilst the rest of the Church was observing the fast of Lent.

Insula Sanctorum et Doctorum or Ireland’s Ancient Schools and Scholars by the Most Rev. John Healy (6th edition, Dublin, 1912), 591-593.

So here we have a Saint Egbert, an Englishman who comes to study in the west of Ireland and who is clearly linked to the Paschal Dating Controversy. Yet the one obvious difficulty in being able to accept Stokes’ identification with our saint is that this individual is said to have died on the very day of Pascha itself, whereas the Irish sources commemorate him on December 8. There is also no mention of this Saint Egbert being one of a number of brothers.

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.