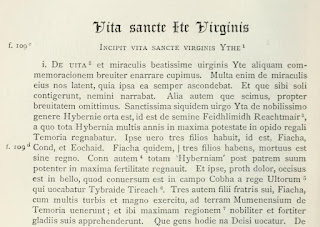

Some fascinating glimpses of the teachings of Saint Ite and of the sanctity she manifested have been preserved in her Life. Here are a few examples taken from Dorothy Africa’s translation of Vita Sanctae Ite from Plummer’s Vitae Sanctorum Hiberniae. The Headings are mine.

Saint Ite is transfigured

2. One day the blessed girl Ita was asleep alone in her chamber (cubiculum); and that whole chamber appeared to people to be burning. But when the men approached it to help her, that room was not burned; and all marveled greatly at this, it was said to them from above, what grace of God burned around that comrade of Christ, who was asleep there. And when holy Ita had arisen from sleep, her entire form appeared as if it were angelic. For then she had beauty such as she had neither before or after. So also her aspect appeared then so that her friends could scarcely look at her. And then all recognized what grace of God burned around her. And after a short interval the virgin of God was restored to her own appearance, which was certainly pretty enough.

An Angel appears to Saint Ite and Testifies to the Holy Trinity

3. On another day when the blessed Ita slept, she saw an angel of the Lord coming toward her, and giving her three very precious stones. And when the handmaiden of Christ had arisen from sleep, she did not know what this vision signified. And the blessed (girl) had a question in her heart about this. Then an angel of the Lord came down to her, saying “What are you searching for concerning this vision? Those three very precious stones which you saw given to you, signify the holy trinity that came to you and visited you; that is a visitation of the Father, Christ his Son, and the Holy Spirit. And always in sleep and in vigils, the angels of God and holy visions will come to you. For you are the temple of the Deity, body and soul.” And speaking these things, he departed from her.

Saint Ite Struggles against the evil one

5. Not long afterward, the blessed virgin Ita fasted for three days and three nights. But in those days and nights through sleeping and vigils the devil openly (evidenter) fought against the virgin of God in many battles. And the most blessed virgin most wisely opposed him in all, as much sleeping as waking. On the second (posteriori) night, then, the devil appeared sad and wailing, and at day break, he departed from the familiar of God, saying in a grieving tone, “Alas, Ita, not only will you free yourself from me, but many others to boot.”

7. And while the blessed Ita was on her way, behold, many demons came against her along the road, and began to contend (litigare) cruelly against her. Then angels of God from above arrived, and fought very hard with the demons for the bride of Christ. And when the demons had been conquered by the angels of God, they fled away through the byways, crying out and saying: “Alas for us, for from this day we will not be able to contend against this virgin. And we wished today to put our claim on her for our injuries; and the angels of God have freed her from us. For she will root up our habitation from many places and will snatch many from us in this world and from the nether regions.” But the virgin of the Lord, with the consolation of the angels of God, meanwhile advanced to the church; and in it was consecrated by the churchmen at angelic order on the spot, and took the veil of virginity.

Saint Ite’s Asceticism

10. The most blessed Ita made great efforts to keep two and three day fasts, and frequently four days. But the angel of the Lord, on a day when she was exhausted by fasting, came to her, and said to her “You afflict your body without measure by these fasts, and you ought not to do so.” But the bride of Christ (was) unwilling to ease her burden, (so) the angel said to her “God has given such grace to you, that from this day until your death you shall have the refreshment of celestial food. And you will not have the power not to eat at whatever hour the angel of the lord will come to you, bringing you food.” Then the blessed Ita prostrated herself and gave thanks to God, and from that bounty (prandium) the holy Ita gave to others to whom she knew it was worthy to be given. And without any doubt she lived thus until her death on the heavenly allotment administered by the angel.

Saint Ite Demonstrates The Gift of Prophecy

12. God even bestowed upon the holy Ita such great grace in prophecy that she knew whether the sick would survive their illness or die.

Saint Ite Heals the Sick and Raises the Dead

14. Then the most glorious virgin of God returned to her cell. And when the familiar of God was nearing her community, she heard from nearby a great and immense wailing. For three dead nobles were there, who had died on that day; and their friends were wailing and mourning for them. And they, knowing that holy Ita was passing by, came down,and asked the familiar of God in a doleful tone that she might come and pray for their souls at least. Holy Ita then said to them: “That thing more that you wish beyond prayer for their souls, in the name of Christ may it happen for you.” They did not know what to make of this speech at that point. The blessed Ita made the statement because she knew, being full of the spirit of prophecy, that it (or she?) in the name of God would revive them from death. Then the holy one went with them to where the dead were, and while praying she marked the prone bodies with the sign of the holy cross; and they arose living at her command. And the bride of Christ asserted (assignavit) that they lived before everyone.

15. In that place there was then a certain paralyzed man in the clutches of a very great illness, and his friends, having beheld the revival of the dead, took him up and brought him to the holy Ita, that she might cure him. For they had no doubt that one who could revive dead men could cure a sick one. Then the familiar of God, observing the great misery of that man, looked to heaven, and said to him: “May God pity you”. And as she spoke, the made the sign of the holy cross on him. Most marvelous to say; when the familiar of God marked the hitherto paralyzed man, he stood up whole and unharmed on the spot before all, as if he had never been seized by paralysis. Then the shout of the whole people was lifted to heaven, praising God, and giving thanks tohim, and glorifying his familiar with deserved honor. Afterward, the familiar of God went on with her companions to her cell.

The Teaching of Saint Ite on What is Pleasing to God

22. At one time the holy Brendan (Clonfert) was asking the blessed Ita about the three works which are fully pleasing to God, and the three which are fully displeasing, the servant of God replied: “True belief in God in a pure heart, the simple life with religion, generosity with charity; these three please God fully. However, a mouth vilifying people (detestans homines), and a tenacious love of evil in the heart, confidence in wealth; these three fully displease God. Holy Brendan and all who were there, hearing such a statement, glorified God in his familiar.

The Teaching of Saint Ite to her Nuns on the Holy Trinity

11. One day a certain holy devout virgin came to the holy Ita, and spoke with her about divine precepts. And while they were conversing, that virgin said to the holy Ita: “Tell us in God’s name, why you are held in higher esteem by God than the other virgins whom we know to be in the world. For to you sustenance from heaven is given by God; you cure all the feeble with your prayer; you speak of past and future events; everywhere you drive out the demonic, daily God’s angels speak with you; you carry on in meditation on and prayer to the holy Trinity without hindrance.” Then the holy Ita said to her: “You answered your own question by saying ‘Without hindrance you carry on in prayer to and meditation on the holy Trinity.’ For who ever shall have done so, will always have God with him, and if I was such a one from infancy, all these things, as you have said, properly pertain to me.” That holy virgin, having heard this speech from the blessed Ita about prayer and meditation on God, departed rejoicing for her cell.

23. A certain holy virgin, wishing to discover in what manner the most holy Ita was living in her most secret place, in which she was accustomed to be free for God alone, went out at a certain hour, in order to see her. She, then reaching there, saw three very bright suns, just as the natural (mundiali) sun lighting up the whole spot and surrounding area. And she was not able to enter out of terror, but at once turned back. The mystery of this portent would be hidden from us, but for the gifts of the holy Trinity, which made everything from nothing, which the most holy Ita assiduously served in body and soul.

The Repose of Saint Ite

36. Afterwards the most blessed patroness Ita was broken by illness; and she undertook to bless and advise her settlement (civitatem), and the clerics and people of Ua Conaill, who had taken her as their patroness. And having been visited by many holy persons of both sexes, amid the choirs of saints, with rejoicing angels in the path of her soul, after the greatest numbers of virtues, in the sight of the holy Trinity, the most glorious virgin Ita passed on most happily 18 days before the Kalends of February. The most blessed body of whom, with many persons having gathered from all around (per circuitum), with many miracles performed, which still have not ceased to be displayed there, most gloriously, after the solemnities of masses, in her monastery which she the very holy Ita, a second Brigit in her merits and morals, established, from the field, was taken (traditum est) to the tomb, reigning with our Lord Jesus Christ, who with God the Father and the Holy Spirit lives and reigns, God in the age of ages. Amen.

http://monasticmatrix.osu.edu/cartularium/life-saint-ita

Content Copyright © Omnium Sanctorum Hiberniae 2012-2015. All rights reserved.